Hebrew title: עולם הסוף

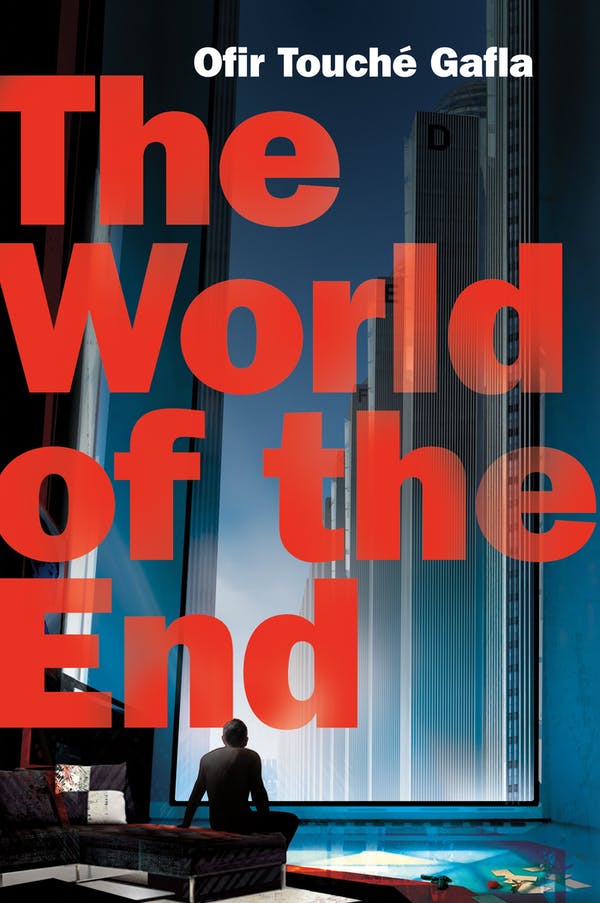

translated by Mitch Ginsburg

Tor Books

June 25, 2013

368 pages

grab a copy here or or through your local independent bookstore or library

The World of the End reminds me of the TARDIS: both are larger on the inside than their outside would suggest. By “inside” and “outside,” in terms of the novel, I mean that the jacket summary (outside) belies the rich and varied story that we find inside (the novel itself). After all, we’re told that this is the story of an Israeli man named Ben Mendelssohn who, after the death of his wife, kills himself so he can rejoin her in the afterlife (if one exists, that is). Upon entering said afterlife, he can’t seem to find that wife, so he engages the services of a private detective. Weirdness ensues.

Just a few chapters into the novel and you’re hooked, or rather stuck, on the ferris-wheel of a plot that is at once engrossing and exhausting, just like the efforts of the protagonist as he runs all over the Other World searching for Marian. And that ferris-wheel reference I just made isn’t random- it’s the reason that Marian is dead in the first place. According to Ben, she was thrown off of the ride by a homeless man while she was on a field trip with her students. Later we learn that the murderer wasn’t homeless at all but a mentally-ill method actor. Nonetheless, Marian is dead and is nowhere to be found in the Other World.

Gafla plunges us unapologetically into this streamlined, highly-organized, efficient Other World, in which everyone lives in the highrise apartment that corresponds to the year, month, day, and time that they died. The dead can travel back in time—that is, to the areas (centuries) that came before. Thus, many dead take these minibuses (that are actually quite large) to the 17th century, for instance, to try out for Shakespeare’s new plays. Because yes, Shakespeare is having a great time in the Other World and has continued churning out the drama.

Most of the dead acclimate themselves to their new existence, but some don’t, and that’s where we ultimately find Marian. But wait…there’s another Marian. One who looks just like Ben’s wife but is…not actually dead. Gafla bounces us back and forth between the real world and the Other World as we follow this other Marian who apparently doesn’t know Ben and has been living in France for most of her life, moving to Israel only recently. The question then becomes: did Ben kill himself for nothing? Did Marian fake her death?

Another metaphor for this novel: when you open a thousand-piece puzzle box and dump the pieces on the floor (the first half of the novel). Then, as you start to put the pieces together, a clearer picture takes shape (the second half). Given the kind of reader and movie-watcher I am, the pieces came together quite late, but that’s likely because I enjoyed the weird suspense of wondering who and what Marian was. Indeed, not everyone in the Other World is a regular dead person. Some hang out temporarily in the Other World when they’re in comas in the real world. Those who died before being born have a special status (they’re called “aliases”) and basically run the Other World. Family trees in this realm are literally trees that are pruned, though in Ben’s family’s case, a renegade alias illegally uprooted his family tree, which is why eight of his family members died in quick succession.

Like I said before, this is just a peek into the complex plot involving two realms, multiple interlocking relationships, and the mystery of Marian’s life/death status. And it brings up larger questions of the afterlife, especially where it relates to Judaism. Though Ben and Marian are Israeli Jews, very little is said about religion in The World of the End, likely because these two are secular. Nonetheless, Judaism, unlike other major religions, has nothing to say about the before-life or after-life in its canonical text (the Torah). References to God and angels are everywhere in the Torah, but nothing about what happens before you’re born or after you die. Rabbis and others over the centuries, though, have discussed the subject, but “Heaven” and “Hell” are not a part of Jewish religious observance. The World of the End never mentions “Hell” or even “Purgatory,” and the Other World isn’t ever called “Heaven.” God is never mentioned, either. Gafla’s egalitarian realm, then, is a fascinating alternative space to which the dead are transported no matter how good or evil they were in life. While this has its advantages, it also means that stalkers who tormented specific people can continue to stalk them if they’re able to find them.

This is the only Gafla book in English translation, but you can find a couple of his stories in translation here and here. I encourage you to read as much Gafla as you can. You’ll be glad you did.