translated by Alex Zucker

original publication (in Czech): 2019

first English edition: 2021

grab a copy here or through your local independent bookstore or library

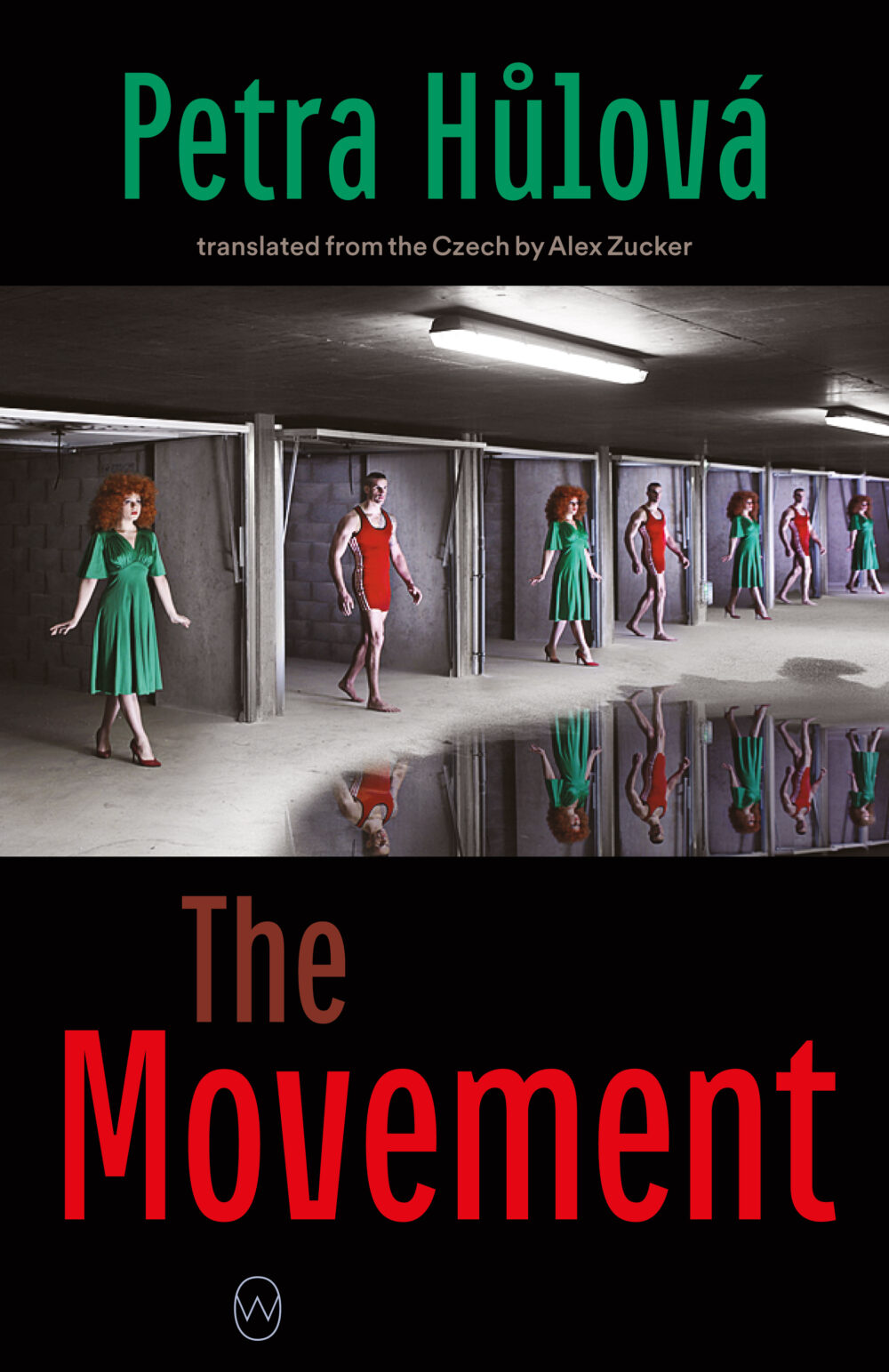

Written in the form of a memoir by a guard at a re-education facility, The Movement is a disturbing story of brainwashing, idealism, and fear. Set sometime in the future when the Internet has been shut down and robots are commonplace, Hůlová’s story focuses on what has occurred in the “New World” (Eastern Europe) since a powerful movement for gender equality took the world by storm.

Begun by a woman named Rita who was profoundly disturbed by the ways in which women have been sexualized, both in public and private spaces, the Movement grew from a few radical women bombing plastic surgery clinics in Eastern Europe to a worldwide struggle for complete equality. To achieve this, re-education clinics accept (and sometimes kidnap) men in order to put them through months- or years-long rigorous training in appreciating women for who they are, not what they look like. This is not just a series of courses or community service, though; rather, these men are treated like animals, made to strip naked at a moment’s notice and forced to masturbate to pictures of older women and women with scars, sagging breasts, and other signs of age. The goal is to change how men think when they look at young, curvy women versus older women. Indeed, their final exam requires that they not get an erection while a bunch of young, naked women dance around them. Some of these men’s wives are even encouraged to go to reeducation centers in order to learn that makeup and plastic surgery are wrong.

Vera, the guard whose memoirs we are reading, is a true believer in the Movement and its goals. She dutifully records how her “clients,” who are given initials and numbers, either pass or fail their various tests. We learn about how the Institute where she works (and others like it) employ many women, and some men, to help usher in a utopia in which men are only attracted to women because of their souls and personalities, not looks.

Running throughout the book, though, are references to the Institute’s former role as a meatpacking facility. Meat hooks still hang from the ceiling, parts of the building retain their freezer-like qualities, and the smell of meat and blood clings to the walls. It is against this backdrop that the narrator tells her story while insisting on how humane and civilized the Movement is. Nonetheless, the descriptions of nameless men packed into cots and herded around against their will makes the meatpacking imagery that much more relevant.

We don’t even learn Vera’s name until near the end of the novel, when she travels to see her mother at a retirement home run by the Movement. During this journey, Vera has what seems to be an emotional breakdown, crying uncontrollably on the bus without articulating to herself or us exactly what is bothering her. Here and there throughout her memoirs, though, she mentions caring about particular clients, or regretting that previous relationships ended. While visiting another reeducation center, she is confronted by another female guard who objects to the Movement’s violent tactics. We get the sense that Vera has accepted everything that the Movement offers so as to hold on to the life that she has, rather than questioning anything and being thrown into an uncertain future. Early on, we learn that she once worked for a place called “PornJoy,” painting fake female bodies for men to have sex with.

Disturbing and depressing, The Movement is a powerful commentary on the lengths people are willing to go to change social norms and achieve an ideal. Alex Zucker’s skillful translation brings this fascinating story to life, reading so smoothly one forgets that the novel wasn’t originally written in English. I look forward to more Hůlová novels and Zucker translations in the future.