translated by Brian Watson and James Balzer

translated by Brian Watson and James Balzer

Vertical

July 28, 2015

240 pages

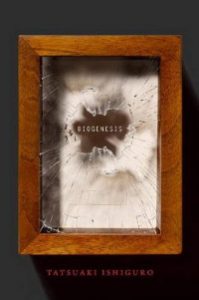

Biogenesis has been called “beautiful” and a “rare treat,” and it is all of these things and more. In the four stories that comprise the book (“It is with the Deepest Sincerity that I Offer Prayers…” & “Snow Woman”- translated by Brian Watson; “Midwinter Weed” & “The Hope Shore Sea Squirt”- translated by James Balzer), Ishiguro explores what happens when a scientist or layperson is irresistibly drawn into a scientific/medical problem. Each story is presented like an official report, the narrative voice sounding dry, official, and objective, and yet somehow also lyrical and mesmerizing. I can honestly say that I haven’t read many books like it (the closest analogue might be Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, but only because Levi also integrates science and a lyrical style).

The volume’s title helps us understand how the stories fit together: “biogenesis” is, after all, “n. the synthesis of substances by living organisms” and “the hypothesis that living matter arises only from other living matter.” Indeed, “life” and “death” are at the heart of each story, specifically the ways in which life persists and even flourishes under bizarre circumstances, and those times when death comes seemingly out of nowhere. As Ishiguro himself explains in the “Afterword,” “loss and rebirth are eternal themes that I’ve pursued.”

The first and longest story of the collection, “It is with the Deepest Sincerity that I Offer Prayers…,” concerns itself with the “winged mouse” and the researchers who delve into the creature’s mysterious biology and path toward extinction. Unlike the subsequent stories, this one appears in a typewriter font, reinforcing Ishiguro’s efforts to make the story seem like an official report. Here, the narrator draws upon written and oral reports concerning the work of Drs. Nobuhiko Akedera and Keiichi Sakakibara on the nature of the winged mouse and why it was bound for extinction, despite the many mysteries surrounding its origins and evolution. Only a few of these mice were ever discovered and caught, and they always seemed to die in pairs. When the researchers attempt to mate the two most recently-found mice, bizarre things happen: the mice seem to glow and even produce tears. Their communication is mysterious, and even their internal organs are extremely odd. As research continues, Dr. Akedera begins riffing on what the mice represent, at one point wondering, “Might not the principle of natural selection close the circle by selecting against all living things in the end? […] Will the truth guide us to preordained harmony or to chaos?” Furthermore, “Dr. Akedera was inordinately fascinated by the fact that everything about the winged mouse, on the genetic level, the cellular level, the specimen level, was headed toward extinction.” What ultimately disturbs him, then, is his belief that the mice might actually live for hundreds of years, and their deaths at this point in time might hint at a larger, looming problem of extinction as the trajectory for all life on Earth, eventually.”

“Snow Woman” comes next, and here we learn about one woman’s strange ability to stay alive despite her extremely low body temperature and heart rate. The army doctor who diagnoses her with “idiopathic hypothermia” (an extremely rare disorder) becomes obsessed with understanding how the condition affects its “victims’ ” lifespans. As in the previous story, Ishiguro suggests that an unconventional biological makeup could give rise to abnormally-long lifespans, but at what cost? The woman, Yuki, seems to hibernate and suffers from nearly total memory loss. Despite traveling around Japan with Dr. Yuhki in an attempt to find her hometown and jog her memory, Yuki only remembers random bits, and thus lives without an identity. As with each of these stories, the scientific investigator is drawn so deeply into the problem that objectivity becomes impossible.

In “Midwinter Weed,” set during World War II, Ishiguro introduces us to a rare plant that thrives on human blood and gives off radiation. When Nakarai, a botany enthusiast, and Harimoto, a research assistant, begin conducting secret experiments on various specimens, involving feeding the plants drops of their own blood, bizarre things start to occur (for example, the plants change color and at times become transparent). And while Nakarai had announced to the Japanese scientific community that he had discovered a plant that could be weaponized, this line of research ultimately comes to nothing. Here, Ishiguro describes a seemingly unusual relationship between humans and plants (the Midwinter Weed “feeds off” of Nakarai and Harimoto’s blood, while the radiation it gives off severely weakens the two men, even as they feel physically compelled to proceed with their research). And yet, we can also read this as an invitation to think more deeply about our biological relationship to the natural world. If species strive for survival, and must adapt to their environments in pursuit of that survival, why not a plant that thrives on human blood?

Finally, while “The Hope Shore Sea Squirt” features a lawyer rather than a scientist, the story’s main concerns are in keeping with the three previous narratives. We learn here about Dan Olson, his wife, and seven-year-old daughter Linda, the last of whom is diagnosed with cancer and given just a few months to live. In trying to make the most of the time they have left with her, Dan and Mary move with her to Hope Shore, a paradise that Linda had once seen in a book. There they learn about the local delicacy- the sea squirt- and how it develops tumors all over its body but has somehow adapted to accommodate them- in other words, symbiosis. Dan gives up everything to study this sea squirt in an effort to find a cure and save his daughter’s life. As in “Midwinter Weed,” it is someone outside of the scientific establishment who is determined to solve a problem or answer a question who ultimately stumbles upon a revolutionary discovery.

In each of these stories, Ishiguro offers us snapshots of determined, driven scientific investigations in which scientists and laypeople become so drawn into their research that they risk losing their objectivity. And yet, it is precisely this loss that leads to fantastic discoveries. The stories themselves follow this pattern: each is told in the third-person, and even though “Deepest Sincerity” and “Midwinter Weed” involve multiple narrative levels, and all are told in a staid and steady voice, they reveal the narrators’ intense interest in the stories they tell. Thus, Biogenesis interrogates how diverse forms of life- humans, sea squirts, plants- exist in a symbiotic relationship far more complex and fascinating than we tend to think.

(first posted on SF Signal 8/25/15)