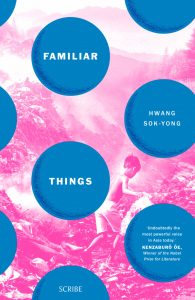

This is a guest post by Anna Ntrouka. You can follow her on twitter @annantrou.

translated by Sora Kim-Russell

translated by Sora Kim-Russell

Scribe Publications

April 26, 2017

142 pages

When recently asked to describe Familiar Things in a nutshell, two things came to mind: first, that it is an endearing book and second, that it is an excellent comment on modern day society. The story spins around a teenage boy, Bugeye, who moves with his mother to a landfill named Flower Island away from the bright lights of Seoul, after his father is arrested and forced to serve time in a “re-education” camp. There, his mother will be able to make a better living than her previous occupation as a street vendor, although this move does automatically mean a step-down in social status.

This is a novel that is built on themes of antithesis, the most prominent of which is definitely the divide between the haves and the have-nots. Hwang Sok-yong wastes no time to set the tone:

“A month has already passed since Bugeye and his mother moved to Flower Island. She had tried to console Bugeye at first by saying that people lived there just like anywhere else, but he knew it was a garbage dump filled with things used up and tossed aside, things people had grown tired of using, and things that were no longer of any use to anyone at all, and that the people who lived there were likewise discards and outcasts driven from the city.”

The residents of Flower Island are indeed outcasts and scavengers. They make do with whatever has been tossed aside, they build their homes from trash, they make feasts out of food that has been found not good enough for glossy Seoul, they clothe themselves rummaging through piles of garbage. One of the most characteristic and quiet ways in which their outcast standing is brought to focus is the fact that nearly all of the characters in the book are never referred to by their actual names, everyone goes by some nickname or another. Bugeye’s mother is always just plain Mother, her companion is the Baron, then there’s Baldspot, Baron’s son and Bugeye’s adopted little brother, as well as a string of other people whose names we never really learn. Even the protagonist’s name is not revealed until way deep into the novel, and still, only when he reminisces about his life before the landfill.

However, a consumerist society and a waste community is only one of the antipodes where Bugeye finds himself caught right in the middle. The transition from his fading childhood to an adulthood that seems rather bleak is yet another contrast he faces. Because he is well-developed for his age, he is deemed capable to work alongside the adults in the landfill, yet he much prefers to spend his time with Baldspot. Children frequently prove to be master escapists in adverse circumstances, and the Flower Island kids are no exception: some of them have devised their very own hideout where they can be free from adults. Baldspot also introduces Bugeye to a family who lives just outside the main landfill “town,” Grandpa Peddler and his daughter, Scrawny’s mama. Scrawny’s mama is a kind soul who has taken in a bunch of rescue dogs —of whom Scrawny, a nervous little yapper has general command.

This is where the speculative fiction wheels start turning. Through Scarwny’s mom, the dokkaebi manifest. The dokkaebi are creatures of the Korean folklore, usually benevolent inhabitants of the spirit world, nothing like the Western concept of ghosts, as they are believed to be spiritual possessions of (usually) discarded items. Yet again, Bugeye finds himself between two worlds, the tangible, smelly landfill and the untouched by time spirit world of Flower Island. It is, of course, entirely fitting that a family of dokkaebi can be found among heaps of items tossed away, except there is a major difference: as Scrawny’s mama says, the spirits come from things that had been loved, not useless throwaways.

Without delving more into the interaction between Bugeye and the dokkaebi, this is a book that holds no major twists. Familiar Things is not so much a plot-driven novel as it is a pensive look on the way we place value, be it on objects, people or life itself. It has an understated air about it and it manages to touch upon the issues it presents with a gentle, endearing touch. Maybe Flower Island is filled with trash, but the promise of flowers still remains.