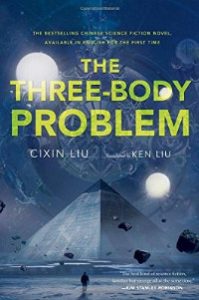

translated by Ken Liu

series: Remembrance of Earth’s Past (Book 1)

Tor Books

November 11, 2014

400 pages

(first posted on SF Signal 11/11/14)

Over the past few months, I’ve been paying more attention to the state of fiction in English translation and have discovered many great publishers and translators. And while the number of contemporary novels translated into English could always be higher, I think we’re headed in the right direction. In terms of international science fiction, writers and translators like Lavie Tidhar and Ken Liu have introduced us to many voices we English-language readers might never have read.

Case in point: Ken Liu’s superb translation of Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem, the first major work of Chinese science fiction available for English readers. Originally published in China in 2006 as 三体 (Three Body), it is just the first in a trilogy, whose official title is Remembrance of Earth’s Past. In the “Author’s Postscript,” Cixin Liu connects the genre of science fiction to a broader international goal, arguing that

[s]cience fiction is a literature that belongs to all humankind. It portrays events of interest to all humanity, and thus science fiction should be the literary genre most accessible to readers of different nations. Science fiction often describes a day when humanity will form a harmonious whole, and I believe the arrival of such a day need not wait for the appearance of extraterrestrials.

The Three-Body Problem takes as its starting point the Cultural Revolution, which swept across China in the 1960s and 1970s. Its program of repression, “re-education,” and violence, in a bid to purge capitalist sympathizers and those not truly devoted to the Communist party, paralyzed the country culturally and scientifically. Out of this chaotic period comes Ye Wenjie, an astrophysicist whose physicist father was killed for not teaching his subject along strictly Communist lines. She winds up at Red Coast Base, a secret military project that sends radio signals into space in an attempt to discover alien life-forms.

Liu jumps back and forth in time, between the end of the Cultural Revolution and contemporary times, inviting us to think about how decades may seem long to humans, but in the cosmic scheme of things, they’re but tiny blips. When Ye realizes one night that her amplified signal has been captured and then responded to by aliens in Alpha Centauri, she chooses to place her hopes on these unknown intelligences to bring order and peace to Earth, whatever the consequences. She encourages them to come to Earth.

These aliens live on a planet called “Trisolaris,” so-called because the three suns that orbit that world are responsible for destroying its civilizations again and again. Their orbits are chaotic, and the result is short “Stable Eras” and frequent “Chaotic Eras,” in which the aliens “dehydrate” and hibernate until a Stable Era returns. Ultimately, the three suns’ gravitational pull damages the planet itself, convincing the Trisolaran leaders that their world is doomed and they must seek a new one.

As the Trisolaran fleet makes its way to Earth, the aliens, in contact with human sympathizers develop a virtual-reality game that introduces people to the problems of Trisolaris, inviting them to solve the “three-body problem” that has plagued Earth-physics for centuries and perhaps save the alien world. As expected, the growing organization of people seeking to meet the Trisolarans splinters into numerous factions, eerily reminiscent of the bloody factional fighting between various Red Guard units during the Cultural Revolution. At the heart of these arguments is the ultimate question: what will the aliens want when they arrive?

I can’t even come close here to evoking the beauty of the translated prose and the fascinating complexity of ideas woven into this story of first contact. What truly struck me was Liu’s decision to describe both the human and Trisolaran reactions to this first “conversation” nearly word for word. Both Ye and the first Trisolaran to receive the Earth’s message “felt this interminable wave [the noise of space] was an abstract view of the universe: one end connected to the endless past, the other to the endless future, and in the middle only the ups and downs of random chance…” (271, 348). When each realizes that a connection has been made, they “rush” to a terminal, check the “recognizability rating” of the received message, and experience “dizzying excitement and confusion“ (272, 348).

It was this clear parallel and the following descriptions of Trisolaran reactions to first contact that reoriented my understanding of the novel’s intentions. On one level, this novel is indeed about alien contact and its ramifications. On yet another level, it’s about the human psyche and how humans view and treat one another. The violence and repression of the Cultural Revolution, Liu suggests, was not a unique moment in Chinese history, but simply one iteration of a basic human craving for power and self-preservation. Liu uses overt repetition and an eclectic narrative structure to focus our attention on these issues.

Liu underscores this in the “Author’s Postsrcipt,” when he points out that while we have no problem killing one another, when we look at the stars, we imagine that the alien life-forms out there must be benevolent. Instead, he suggests,

Let’s turn the kindness we show toward the stars to members of the human race on Earth and build up the trust and understanding between the different peoples and civilizations that make up humanity. But for the universe outside the solar system, we should be ever vigilant, and be ready to attribute the worst of intentions to any Others that might exist in space. For a fragile civilization like ours, this is without a doubt the most responsible path.