Graham Oliver’s work has previously appeared in Electric Literature, Harvard Educational Review, Ploughshares‘ blog, and elsewhere. He lives and teaches near Austin, TX.

translated from the Polish by David French

May 22, 2018 (originally published in Polish in 2013)

432 pages

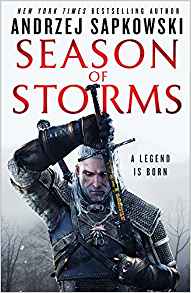

Like many of Sapkowski’s American readers, I came to the Witcher books because of the video games. The series stands out in the video game medium for having engrossing, complex, meaningful stories that few other games can measure up to. 2015’s The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt won pretty much every award it could, including several for best role-playing game and best storytelling. The stories the games tell have their flaws, of course, but overall they were some of the best narrative experiences I’ve had in gaming. Season of Storms leans into the games’ success: the cover features the games’ depiction of Geralt as the cover.

The books and games (as well as a comic book series, a poorly received Polish television and a forthcoming Netflix series) follow Geralt of Rivia as he stumbles his way reluctantly into the middle of political intrigue, plots for world domination, and general magic-fueled shenanigans. Geralt is a witcher, an alchemically- and magically-enhanced monster hunter. His mutations grant him strength, speed, longevity, while also making him (depending on the needs of the story) nearly unable to express emotions and infertile. While Season of Storms is the most recently published book, it falls early in the chronology and is set around the time of the short stories contained in Sapkowski’s first Witcher book, a collection of short stories from 1993 entitled The Last Wish.

Season of Storms takes place in Kerack, a small kingdom I hadn’t remembered encountering before this book. That’s one of the things I love most about the series: the vastness of the world. Not in terms of physical size, but in terms of how the series’ storytelling constantly reminds you what a small slice the audience gets to see. The stories allude to events, places, and people the audience has never encountered, but it treats those allusions as they would occur in the natural world, not taking a break to explain them as though Geralt has amnesia and can’t remember his past life (side note: Geralt frequently has amnesia and can’t remember his past life). Characters show up and greet Geralt with lines like, “I haven’t seen you since that important battle!” and Geralt makes a quip and the story moves on and I absolutely love those moments because they do what all great high fantasy does: gives you a sense of a larger world waiting to be discovered, just past the edges of the page.

Unfortunately, while the macro world building of the Witcher is delightful, the specifics often don’t measure up. Geralt hits annoying levels of perfection. He’s more skilled at fighting than pretty much anyone else, he figures things out faster, and every woman he encounters wants to sleep with him (which, paired with his chemically-subdued emotions, makes for a weird commentary on masculine bravado). Nearly every other major player in the world is consumed with a lust for power. Magic’s danger is underestimated, the common folk are neglected, and Geralt is the one person just trying to do the right thing. In order to put him into a position where he is the underdog with obstacles to overcome, the narrative almost always relies on Geralt’s one adorable flaw: he’s just too darn trusting of other people. Season of Storms’ entire story relies on this over and over again. Condensed, the story is a series of people telling Geralt, “Wow, you shouldn’t have trusted them!”

In a video game, Geralt’s Mary Sue-levels of perfection work because that’s what we expect from a video game protagonist. The games also temper Geralt’s machismo by keeping his dialogue sparse. In Season of Storms, though, these characteristics burst through annoyingly. Geralt launches into long diatribes, peppering his speech with jarring Latin and French phrases then a short time later referring to a jail as “the slammer.” In a fight, we’re told what specific nerve above the ear he delivers a pinpoint blow to. He’s literally described by a woman as one of the few “real men” she’s encountered. On top of this, the story has the classic, overly familiar trope of the villain spending an absurd amount of time explaining his master plan while Geralt is seemingly incapacitated but, wait, he’s not fully incapacitated and the villain’s speech gave him the time he needed to recover!

I’ll probably continue to occasionally pick up one of the books. I might even make it to comic series one of these days. But that desire to keep reading is anchored firmly in the narrative experience of the games, an experience that the Witcher books I’ve read so far have not lived up to. Season of Storms is, unfortunately, not an exception.