translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

May 24, 2016

224 pages

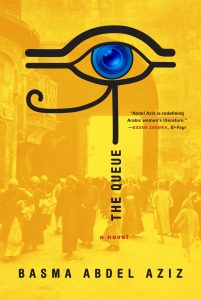

There aren’t any starships or spirits in The Queue; no mutant alien viruses or Martian colonies, either. And yet, it is speculative fiction, because Basma Abdel Aziz has taken the reality of Egypt’s oppressive security apparatus and its impact on people’s lives and distilled it into a chilling Orwellian/Kafkaesque/Murakamian horror story. After all, the unbreachable, imposing Gate (from which rules and laws are handed down) and the queue that forms from it (of people waiting to enter for permission slips and certifications and signatures) act as invisible magnets, pulling more and more ordinary people into its sphere until an alternate society coalesces around it.

At the heart of the story is Yehya, a young man who is shot by Egyptian security forces while witnessing a street protest (called the “Disgraceful Events”) against the increasingly oppressive power of the government. Almost immediately, Yehya runs into trouble- the bullet cannot be extracted, he’s told, unless he gets special permission from the Gate. And so he joins the queue. As time passes, he gets sicker, but he keeps waiting, and the Gate never, ever opens.

Abdel Aziz meticulously and masterfully explores what happens when people like Yehya, who are waiting for official signatures, certifications, and other documents, begin to coalesce into a kind of sub-community, one built around a shared hope that the Gate will one day reopen and issue the documents that people need. But all that emerges from the Gate are orders, rules, regulations, condemnations, and declarations (including one that refuses to admit that any bullets were fired during the Disgraceful Events). Bureaucratic doublespeak and circumlocution (for instance, “you need a signature to show that you are allowed to receive a document,” etc.) catch the people in the queue in a kind of temporal eddy, until they seem to have forgotten why they consistently return to the it after work or why they never leave at all. One of Yehya’s friends, a former philosophy lecturer, considers this situation:

He wondered what made people so attached to their new lives of spinning in orbit around the queue, unable to venture beyond it. People hadn’t been idiots before they came to the Gate with their paperwork. There were women and men, young and old people, professionals and the working class…Everyone was on equal ground. But they all had the same look about them, the same lethargy. Now they were even all starting to think the same way. (90)

As a kind of frame for this story, the doctor who refuses to operate on Yehya without official permission begins to feel remorse, and obsessively reads Yehya’s file, which is updated daily by an unseen hand. While the doctor isn’t physically in the queue, he begins to live like he is, caught between wanting to help a seriously ill patient and fearing government repercussions.

It is only Yehya’s girlfriend(?) Amani, his friend Nagy, and a friendly journalist named Ehab who question and defy the Gate in the hopes of saving Yehya. You find yourself rooting for them like you would for a helpless insect getting sucked down into a whirlpool.

For a fantastic roundable discussion about this book, which goes into much more depth, check out “Let Loose Your Tongue”: A Roundtable on Basma Abdel Aziz’s The Queue at The New Inquiry. We need more novels like this, and I hope that Abdel Aziz keeps writing and reminding us that external oppression fosters internal oppression- we must resist both.