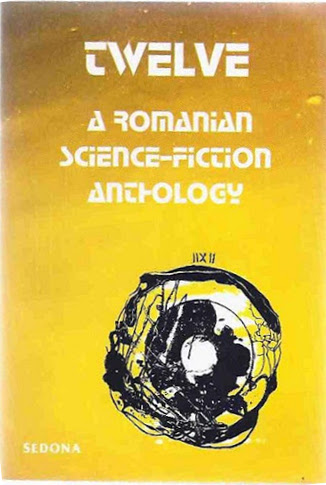

selected and introduced by Cornel Robu

selected and introduced by Cornel Robu

Sedona Publishing House (Timişoara, Romania)

1995

more information about the anthology here

Stories included (in order of original Romanian publication):

- “Igor’s Mannequin” (1938) by Victor Papilian, tr by Virgil Stanciu

- “Tristan’s Last Avatar”/ “The Last Avatar of Tristan the Old” (1966) by Vladimir Colin, tr by Mihaela Avrămuţ

- “Les Trois Grâces” (1976) by Mircea Eliade, tr by Mihaela Avrămuţ

- “The Judges” (1976) by Mircea Opriță, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

- “Algernon’s Escape” (1978) by Gheorghe Săsărman, tr by Virgil Stanciu

- “The Neuhof Treaty” (1980) by Ovid S. Crohmălniceanu, tr by Ioana Robu

- “Phenotype of Mist and Drops of Nothing” (1981) by Mihail Grămescu, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

- “Modern Martial Arts” (1982) by Alexandru Ungureanu, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş

- “Prosthesosaurs” (1983) by Gheorghe Păun, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

- “Omohom” (1987) by Cristian Tudor Popescu, tr by Ioana Robu

- “The Shakespeare Variant” (1988) by Silviu Genescu, tr by Antuza and Silviu Genescu

- “Haustoria” (1989) by Lucian Ionică, tr by Dana Andreea Chetrinescu

Twelve is a remarkable anthology. Unfortunately out of print and difficult to find online, it is a testament to the talent and creativity of Romanian authors who have written speculative fiction since the 1930s, under the shadow of censorship. The names listed above are quite recognizable to Romanian readers, though Anglophone readers have not heard of most of them. This is mainly due to the stranglehold of communism and totalitarianism on the country that lasted from 1947 to 1989, when Romanians succeeded in overthrowing dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. As Twelve‘s editor Cornel Robu says of Cristian Tudor Popescu’s “Omohom,” for example, the story “lingers in the reader’s intellectual memory by its desperate message sent from the no-way-out inferno which was Romania before December 1989 under the communist dictatorship.” Several of these stories remark obliquely on the destruction wrought in Romania by totalitarianism via social and intellectual control, much like Stanislaw Lem and the Strugatsky brothers’ work condemned similar political situations in Poland and Russia through the lens of science fiction, allowing them to dodge the censors.

Just two of these stories take place off-planet, while the other ten explore ethical and scientific questions in the context of an evolving human society. Papilian, Colin, Eliade, Opriță, and (to some extent) Săsărman all grapple with how power over the natural world or a deep understanding of human physiology and psychology can give those who wield it immense destructive capabilities. Grămescu, Ungureanu, Păun, and Popescu take as their central theme the unique threat that advanced technology poses to humanity; while Crohmălniceanu and Ionică offer us works of body horror (as we call it today) in the context of alien/viral invasion and biological manipulation, respectively. Finally, Popescu and Genescu set their stories somewhere other than Earth, even as they comment on problems of social engineering and technology that is easily applicable to our own planet.

Below I go into more detail about each of these stories and their authors in the hopes that all of you reading this review and following Romanian SFT Month will seek out and read more Romanian speculative fiction in English (and in Romanian, if possible!).

* * *

“Igor’s Mannequin” (1938) by Victor Papilian, tr by Virgil Stanciu

Papilian (1888-1956) was a professor of human anatomy at the Medical School of the University of Cluj. Considered a “mainstream” writer who also wrote sf, he was also a theater director and literary patron.

“Igor’s Mannequin” is a chilling story about a mad scientist (Voronyuk) who kills convicts and captures the images of those they loved most in life just before death. The narrator, a friend and war buddy of Voronyuk, first hears his strange theories at a scientific congress: “memory was not a brain function, but a function of the sensors, of the eye, ear, nose, and skin required, no doubt, the guts of a poet or of a madman…According to him, visual images were stored in the eye-chamber (like slides in a projector), auditive images were stored in the ear (like songs recorded on score-sheets), tactile ones in the skin and so on. The brain was but a motor the only function of which was to flick these images on instantly, as needed—just like a chessplayer handles his pieces, but at a cosmic speed” (13). According to Voronyuk, “when a man dies, the most endeared face remains engraved in his memory….the eyes are the venue of the memory of visual images and as a dear face has a material existence, a picture of it can be taken from the retina. I have construed a highly sensitive camera which, applied on the eye in the brief interval between being and nonbeing, takes a picture of that face, thus peremptorily proving my theory” (15-16). As the narrator explains, Voronyuk becomes so obsessed with his theory that murder means nothing to him anymore, to the extent that he kills his own lover just to learn with whom she was having an affair.

“Tristan’s Last Avatar”/ “The Last Avatar of Tristan the Old” (1966) by Vladimir Colin, tr by Mihaela Avrămuţ

also available in English:

“The Contact,” translated by the author (Other Worlds, Other Seas, 1970).

“Beyond,” translated by ? (Edge, Autumn/Winter 1973).

“Within the Circle. Closer and Closer,” translated by ? (Jurnalul SF #72-73, 1994).

Colin (1921-1991) was an sf author and editor, well-known abroad, especially in France. He wrote fairy tales, fantasy, and “science fantasy.”

“Tristan’s Last Avatar” is an intriguing nested story about a biographer (the narrator) researching the mysterious disappearance of a sixteenth-century French alchemist named Tristan le Vieux, who refused to turn a large amount of lead into gold for King Henry III of Valois. According to a contemporaneous biography of Tristan (which the narrator is reading), when the Swiss guards came to kill him on the order of the king, Tristan declares himself a free man and vanishes into thin air. We, the readers, are then transported into the place to which Tristan actually escaped: the fourth dimension, which the alchemist had searched for his entire life. There, he is met by an old sage named Mirgh, who confesses that he has watched over Tristan’s work for years and guided him whenever possible. Mirgh gives Tristan the ability to visit his own past and future, and in the latter he witnesses the writing of his own biography by the very narrator who opened the story itself–a deft use of the mise en abyme technique.

“Les Trois Grâces” (1976) by Mircea Eliade, tr by Mihaela Avrămuţ [also published in English in Tales of the Sacred and Supernatural, 1981]

also available in English:

“Gypsies,” translated by Ana Cartianu (Romanian Fantastic Tales, 1981 / Tales of the Sacred and Supernatural, 1981).

“Twelve Thousand Head of Cattle,” translated by Eric Tappe (Fantastic Tales, 1969).

“A Great Man,” translated by Eric Tappe (Fantastic Tales, 1969).

“Midnight at Serampore,” translated by William Ames Coates (Two Tales of the Occult, 1970).

“The Secret of Dr. Honigberger,” tr by William Ames Coates (Two Tales of the Occult, 1970).

The Forbidden Forest, translated by Mac L. Ricketts and Mary Park Stevenson (University of Notre Dame Press, 1978).

Youth Without Youth and Other Novellas, translated by Mac L. Ricketts (Ohio State University Press, 1988).

Eliade (1907-1986) was a historian of religion (comparative religion) and author of some of the most important works in the field. Eliade studied at the University of Calcutta from 1928-1931, and from 1956-1986, he was Professor of the History of Religion at the University of Chicago. Considered a “mainstream” writer who wrote science fiction and fantasy. According to Cornel Robu, Eliade “extrapolates in a sciencefictional manner various hypotheses drawn from Indian doctrines and esoteric practices such as Yoga and Tantra.”

“Les Trois Grâces” was written in Paris and appears in its first English translation in Twelve. According to Eliade (and noted by Robu), the author explores an idea he found in the “Apocrypha” of the Old Testament and transforms it into a mutant story. First introduced to this occult doctrine of Apocrypha by an old monk, Dr. Aurelian Tătaru comes up with a rejuvenation treatment that he gives to three old women suffering from cancer. Set in 1950s Romania, its people imprisoned behind the Iron Curtain and at the mercy of the Secret Police, the story picks up after the treatment is suddenly stopped and forbidden by government order. As one former colleague of his explains, “Tătaru is alleged to have once said in public that, in Paradise, Adam and Eve were periodically regenerated, that is rejuvenated, through cancerous tumors. And that—only after the original sin did the human body lose the secret of periodical rejuvenation, that is youth everlasting; and that ever since whenever the human body tries—suddenly and strangely anamnestic—to repeat the process, the blind proliferation of cancerous cells ends in malign tumor…” (34). Dr. Tătaru destroys all his notes before moving to another hospital, while the three women are abandoned and condemned to grow old in the autumn and grow younger in the spring. When Dr. Tătaru meets up with a couple of old friends near the old hospital many years later, he dies under mysterious circumstances, which results in the Secret Police visiting his friend Filip Zalomit and questioning him in order to find out the secret to rejuvenation that Tătaru had discovered. We ultimately learn that Tătaru had encountered one of the Three Graces during her youthful period and was so terrified that he fell down a steep hill and died. Zalomit decides to commit suicide when the Secret Police come to him to demand the secret to rejuvenation.

“The Judges” (1976) by Mircea Opriță, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

also available in English:

“Sign of the Unicorn,” translated by Cezar Ionescu, Gabriel Stoian and Pia Luttmann (Nemira ‘94]

Opriță (b. 1943) was staff editor at Dacia Publishing House from 1972-74 and became secretary of the Writers’ Union Cluj Branch and president of the Syndicate Association Writers in Cluj in 1995. He published five collections of sf stories, realistic novels, the first Romanian book-length study of H. G. Wells, and a massive study of Romanian sf from its origins to the end of the twentieth century (The Romanian Anticipation, 1994).

A lowly researcher, haunted by his humorous surname and the jokes at his expense because of it, pressured by his cold wife to move up the ladder at his research institute, and laughed at by his colleagues for his inability to produce the results he has promised them, Budulău is visited in his lab by two men from his future, who warn him that the gelatinous substance he will discover (by adding a specific catalyst to water), will result in an apocalypse. Apparently, it will be loaded into bullets and used to kill people by turning their insides into gelatinous paste. Even before Budulău can do anything beyond think about the consequences of any action he takes, one of the future men returns (looking like he’s been in a battle) and kills the researcher, “the man paradoxically killed by a weapon he hadn’t invented yet and would never invent” (130).

“Algernon’s Escape” (1978) by Gheorghe Săsărman, tr by Virgil Stanciu

also available in English:

Squaring the Circle: A Pseudotreatise of Urbogony: Fantastic Tales, translated (from the Spanish version) by Ursula Le Guin (Aqueduct Press, 2013). “Sah-Harah” is available to read here]

Săsărman (b. 1941) is a Romanian architect, author of a book on the theory of architecture, and literary editor and commentator. Has lived in Germany since 1983 and writes science fiction.

“Algernon’s Escape” won the Europa Award at the 5th Convention of the European Society of Science Fiction (Eurocon, Stresa, Italy, 1980). The pretext comes from Daniel Keyes’s “Flowers for Algernon” (short story- 1959; novel- 1966). Narrated by a journalist who is sent to a genetic-engineering laboratory on Owl’s Island, the story follows that journalist as he becomes trapped there once an experimental mouse named Algernon escapes from the lab (and tries to hide in the journalist’s hotel room). A carrier of a virus that turns only those with low intelligence into diabolical geniuses, the mouse infects the human population at a dizzying speed. Only those people with inborn intelligence and good sense are immune. Eventually, the journalist realizes that his sudden ability to decipher a complicated linguistic puzzle given to him by the head of the lab means that he, too, has been infected with the virus. He then wonders: “What could have been the consequences of a long-time-several generations-epidemic at planetary scale? At first sight, they could only be positive; after all, the entire evolution of the human race had stood under the sign of an intellectual boom, which meant that any further advance in that direction had to be seen as consonant with the progress vector. Provided, of course, that there were sufficient guarantees that there were no harmful side effects, that in its impetuous march across the planet virus G did nothing but stimulate the intellect in an irreversible way. The laboratory research David conducted was far from producing such guarantees, as I well knew…But even if one granted the feasibility of such an ideal variant, was a general contamination to be wished for? Was what for the abstract human being represented an unquestionable progress good for every real individual and for society as a whole?” (106). The journalist quickly sees how badly things can get when an obscure, dim-witted sergeant stationed on the island becomes infected and turns the entire place into a nightmarish prison colony, with plans to unleash an army of genius mice to infect the entire world. Though the journalist manages to get a note back to his editor explaining what is going on at the lab, the editor doesn’t take his employee’s words very seriously.

“The Neuhof Treaty” (1980) by Ovid S. Crohmălniceanu, tr by Ioana Robu [also included in The Road to Science Fiction 6, 1998]

Crohmălniceanu (1921-2000) (born Moise Cahn/Cohn) was one of the most influential literary critics during the mid-twentieth century and an author of science fiction. He promoted socialist realism but also helped writers banned by the Communist Party find publishers. Crohmălniceanu also worked as a professor of the history of Romanian literature at the University of Bucharest. Started writing sf in the 1980s, at the same time as the “new wave” writers, but coming at the work as a member of the older generation.

“The Neuhof Treaty” was written just a few years after the first appearance of the word “nanotechnology” (1976) in the West, despite the fact that very little Western scientific research filtered through the Iron Curtain. Crohmălniceanu imagines here a kind of technology that would eventually characterize what we think when we hear the term: “intelligence and willpower, capacity of self-reproduction, cooperation towards a common goal, inexhaustible energy, invulnerability, invisibility and impossibility of being in any way visualized” (Robu). The story opens with a series of questions about the nature of a creature/technology that has taken hold of a certain Martin Neuhof–a kind of Everyman with no particularly distinguishing characteristics: “Rational, inhuman beings of very small proportions? Intelligent bacteria? Viruses having this property which belongs only to the advanced forms of life? Enzymes, pure energies, psi waves?—nobody on Earth knows. There is one certain fact, that whoever or whatever they are, their residence is in Neuhof” (70). At first, Neuhof assumes that he can recover from illnesses and accidents easily because he is lucky, but he eventually realizes that this luck is superhuman (after all, he not only survives being shot but the wounds themselves disappear within a matter of days). In time, the government gets involved, and then leaders around the world, all focused on what to do with Neuhof, whom they fear might turn dangerous. Neuhof himself is, ironically, the least interesting character in the story. It’s unclear throughout if he ever understands how to actively heal himself, though it becomes clear, thanks to his shady insurance dealings, that he eventually realizes that he cannot die. The organisms/energies inhabiting his body first show their intelligence by communicating via a rash on his body to the scientists who are trying to kill him (thinking that this is the only way to keep the world safe). After communicating with the scientists over a number of years, a treaty is hammered out between the “organisms” and humanity, resulting in the agreement that Neuhof is to be kept alive and happy permanently, lest the “organisms” kill off humanity.

“Phenotype of Mist and Drops of Nothing” (1981) by Mihail Grămescu, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

also available in English:

“The House,” translated by ? (Jurnalul SF #72-73, 1994).

“The Songs of the Libelungs,” translated by Cezar Ionescu, Gabriel Stoian and Pia Luttmann (Nemira ‘94).

Grămescu (b. 1951) is considered one of the “new wave” Romanian science fiction writers of the 1980s.

“Phenotype of Mist and Drops of Nothing” is a short monologue given by a man who criticizes other men he knows who took advantage of a new technology that literally sucked the life out of the woman with whom they were all in love (Annie). These objects were “small mechanisms resembling cameras, which stole the LIVE image of the person toward which they were pointed: small gadgets which, within the pearl of nothing, stored ectotypes that could be looked at any time after that: captives in the little balls of some toys” (149). People thought that it was a harmless gadget, but eventually the narrator realized that Annie had wasted away and died because of it, since so many men were obsessed with her.

“Modern Martial Arts” (1982) by Alexandru Ungureanu, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş [also published in English in Nemira ‘94]

Ungureanu (b. 1957) was an engineer in Bacău until 1989, when he decided to become a journalist. He published a novel of linked stories called The Great Threshold in 1984. “Modern Martial Arts” won first prize in the 1982 Helion story contest and was first published in its November 1982 issue, then reprinted in Almanah Anticipatia.

Part of the Romanian “new wave,” Ungureanu crafted “Modern Martial Arts” as a far-future galactic story featuring Japanese martial arts. The weapons used in this kind of fighting are brought to Earth from around the galaxy. Fighters do not physically interact with one another but via their “videoplasms”: identical copies of the fighters who actually do physically interact. Normally, a few minutes after the fight, these copies (who are self-aware and have the same memories as their originals) disintegrate. In this story, one of the protagonist’s clones shocks the audience and his videoplasm opponent by outwitting the latter and killing him, and then killing the original, as well. As punishment, the original whose clone committed that crime is cloned multiple times and must fight these copies of himself.

“Prosthesosaurs” (1983) by Gheorghe Păun, tr by Linda Harris-Marcoş and Ioana Robu

Păun (b. 1950) has a doctorate in mathematics and has worked as a mathematical analyst with the Computer center at Bucharest University. Has published two collections of science fiction stories. After 1989, Păun wrote a “sequel” to Orwell’s 1984.

In the world of “Prosthesosaurs,” people have started replacing their organs with artificial ones, but soon those with too high a percentage of artificial organs have their civil rights revoked and are placed in facilities and kept alive only to have their major organs eventually harvested for transplant into other people. A journalist (Arnod) gets admitted into a secret meeting where scientists and politicians are debating a proposed law that would raise the artificial organ limit, which would enrich the artificial organ manufacturers and those politicians receiving kick-backs. As Arnod learns, in order to push this law through, some leaders are hiring hit men to attack those opposed to it in order to force them to get more artificial organs and then support the law. Arnod becomes a victim of this kind of attack

“Omohom” (1987) by Cristian Tudor Popescu, tr by Ioana Robu [also included in Worlds and Beings, 2015]

also available in English:

“Cassargoz,” translated by Cezar Ionescu, Gabriel Stoian and Pia Luttmann (Nemira ‘94)

Popescu (b.1956) worked as a computer analyst and programmer in Bucharest until 1989. Since 1990, he has worked as the second editor and editorialist of a daily newspaper. Popescu won the European Society of Science Fiction Prize in 1987 for his collection Planetarium.

“Omohom” is the eponymous name of a planet on which humans settled eons ago. When children on the planet turn ten years old, they come down with a mysterious disease that can only be cured by a machine located somewhere in the desert. Most children are cured and return to their families, but the price is the ability to exercise their intellect and the ability of the people as a whole to evolve intellectually and socially. In this story, a father watches over his ill son and reads to him from a book that bemoans what has happened to the people of Omohom: “Sometimes, I hate the Engineer with all my heart. And other times, I think maybe he’s not so guilty as he seems; he wanted to give men Paradise and—after all—nobody can say he didn’t succeed. Omohom is the only planet inhabited by man which will last as long as the solar system it is part of. Numberless human worlds will have perished by then, destroyed by men. What importance has the pain of one single man in the face of a whole planet bathed in happiness?” (171). Eventually, the father brings his son to the machine and leaves him there for the required amount of time, hoping that his son will return to him. A beautiful, lyrical story.

“The Shakespeare Variant” (1988) by Silviu Genescu, tr by Antuza and Silviu Genescu

also available in English:

“Glimpses of a Faraway World,” translated by Cezar Ionescu, Gabriel Stoian and Pia Luttmann (Nemira ‘94).

“MMXI,” translated by ? (Galaxy 42: Collected Stories (2), 2020 / Worlds and Beings, 2015).

“Transformation,” translated by Antuza Genescu (East of a Known Galaxy, 2019)]

Genescu (b. 1958) was a draftsman in Timişoara until 1989, after which he became a journalist. He has also worked as an editor at the Marineasa Publishing House. Genescu published numerous sf stories and one collection.

“The Shakespeare Variant” takes place on a spacecraft on its way to Ariel (one of Uranus’s satellites), which carries a crew trained to drill into it and install the most sophisticated computer system in the galaxy. The ship’s own onboard computer is programmed to respond to the crew and passengers with the personality of Mae West. The narrator, who captains the ship and was paralyzed from the waist down during a conflict years before, becomes annoyed when a German cameraman tasked with filming the operation on Ariel tries to befriend him. Eventually the cameraman proposes that everyone on board entertain themselves by acting like the exact opposite of themselves; the computer unexpectedly joins in the fun and adopts the persona of Ophelia from Hamlet, leading to a very expected disastrous ending. This story includes one of my favorite lines of the collection: “Whenever I’d let my thoughts wander, time slipped away from me. I would find it later, a ball of crumpled useless hours” (193).

“Haustoria” (1989) by Lucian Ionică, tr by Dana Andreea Chetrinescu

also available in English:

“Among Other Mornings,” translated by Magda Groza, Mihaela Mudure, Alexandru Solomon and Samuel Onn (Worlds and Beings, 2015)

Ionică (b. 1952) is a graduate of the Faculty of Philosophy of Timişoara and the Institute of Cinematography of Bucharest. He has made several documentary and scientific films. As of 1995, Ionică was a lecturer at the Faculty of Journalism at the University of Timişoara and has published a collection of short sf stories and one work of non-fiction.

In “Haustoria,” the protagonist leaves his cold and unloving wife and two children to check himself into some sort of institution. There, he meets an old classmate-turned-scientist who proceeds to “plant” seeds on the protagonist’s body. Eventually, we learn that the unnamed man has agreed to go to the institution in order to give back to humanity and feel like he’s made a difference in the world. Once the plants grow on his skin (using his blood and organs as fertilizer), they are harvested and used to treat a dying man who’s been badly burned. (The word “haustor” is defined in a footnote: “sucker-like organ by means of which some parasite plants suck in food from their host”). We witness the protagonist’s thoughts shift into a less anxious, more serene style over the course of the story and it concludes after the plants have all been harvested from his body and he walks out into a garden, an act symbolizing his death.